Anal Fistula

An anal fistula is an abnormal tunnel running from the outside skin in the anal area, through the anal muscles, and opening onto the inside lining of the anus. Although rare, anal fistulas are often encountered in a colorectal clinic. Overall, one person in 10,000 will develop an anal fistula. Those affected tend to be aged 20–40 years, with men developing the condition twice as often as women.

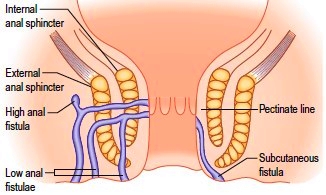

A third of people develop a fistula after having had an anorectal abscess. This may be immediately after the abscess has healed or been treated surgically, or it may appear many years after the abscess has healed. The cause of both these conditions is infection of an anal gland. The anal glands sit in between the two circular sets of anal sphincter muscles and their secretions are released into ducts that cross the internal anal muscle and open into the anus. When an anal gland becomes infected, an abscess can form in between these two sets of anal sphincter muscles. Eventually, the abscess discharges pus, and if it discharges in two directions (through the skin and through the anus), a fistula will form. The anal gland infection does not heal, so the abscess can recur.

Anal fistulas can also be caused by Crohn’s disease and more serious conditions such as cancer.

An anal fistula can cause recurring pain and is often associated with a discharge. The discharge can lead to itching around the anal area, and some patients also develop recurring infections around the anus, as happens with an anorectal abscess.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is usually made in the outpatient department when the surgeon sees an opening onto the skin around the anus. Often there is redness around the area, and sometimes if pressed, a discharge can be induced. It may also be possible for the surgeon to find the internal opening. This examination should not be painful, but may cause some minor discomfort. If it is painful, an examination under general anaesthesia can be performed.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the area can be very useful, especially for a complex fistula, but sometimes the diagnosis can only be made by examination under anaesthesia in the operating theatre.

Surgical treatment

Sometimes the fistula is so minor that both the patient and surgeon are content to leave it alone. However, for patients who are having ongoing problems with their fistula, surgery is the only option. A fistula may be treated surgically in one of several ways according to its complexity.

- Fistulotomy, which opens the length of the fistula to the skin surface, allowing the open wound to heal slowly. Fortunately, 19 in 20 people have a so-called “low” fistula, ie, one located at the bottom of the anus and involving very little muscle, so when the fistula is laid open, the loss of muscle is so minor that there are no problems with continence. Fistulotomy is frequently performed for a low fistula and has a good long-term cure rate.

- One in 20 people have a so-called “high” fistula, where there is so much muscle involved in the fistula that there would be a high risk of incontinence if this was to be laid open. When this is found during surgery, the first choice is Seton placement. A Seton is a suture (stitch) that is introduced into the fistula and runs along its entire length, allowing it to drain from the inside out. Many patients are happy to live with the stitch permanently if their symptoms are minor. However, if the stitch causes significant issues or symptoms persist, further therapy can be considered. Merely leaving the stitch in place is beneficial for healing in some people. Some people’s bodies respond to placement of a Seton stitch by trying to push it out, and on follow-up we find that the fistula has moved from a high position to a low one that can be treated safely by fistulotomy.

- For people in whom a Seton is still troublesome or is not working its way out, we can proceed to a surgical fistula repair, the aim of which is to close the internal opening of the fistula and preserve the anal sphincter muscles. This is a more complex operation. There are several options available, but the best results are likely to be achieved by an advancement flap repair, which involves closing the internal opening of the fistula with a layer of either anal mucosa (a mucosal advancement flap) or with some anal skin (an anal advancement flap). Other options are fibrin glue injection, a fistula plug, or a LIFT procedure, which entails tying off the fistula between the sphincter muscles.

In patients who already have weak anal muscles, any treatment of an anal fistula is done very carefully and cautiously. None of the treatments available can guarantee success and all have a complication rate. Further, it is inevitable that any infection or condition affecting the anus has the potential to impact on bowel continence. Where there is a high fistula, ie, one that involves a significant amount of muscle, the surgeon and patient spend a considerable amount of time discussing the benefits of surgery versus the risk of incontinence.

For more information on anal fistula, visit www.nhs.uk/conditions/Anal-fistula/Pages/Introduction.aspx